Liposome Production for Vaccines Using 3D Printed Microfluidics

Research project on vaccine production using 3D printed microfluidic devices.

Samuel was commended for this innovative project that combined 3D printing with microfluidics to create a low-cost vaccine production medical device. This microfluidic system is designed to support future drug delivery methods that use GPS-like targeting inside microscopic liposome droplets. With this approach, medication can be directed to a specific organ or tissue, such as the pancreas, kidneys, lymph nodes, or a tumor site, before the drug is released.

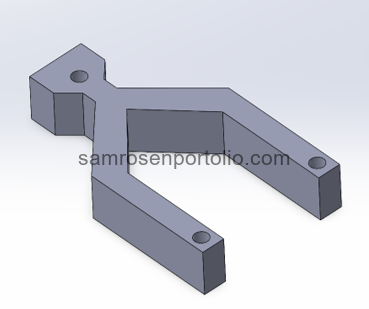

Figure 1 – CAD Model designed in SolidWorks.

Targeted delivery helps avoid first-pass metabolism, which is the process where the liver breaks down medication before it can reach the rest of the body. Reducing this early breakdown increases the potency of the treatment and decreases unnecessary work for the liver.

Figure 2 – Sheep blood syringe injection through the device to evaluate flow behavior and channel performance.

Figure 3 – Sheep blood injected through the device to evaluate flow behavior and channel performance.

The device I created produces uniform and stable liposome droplets using a low-cost microfluidic device fabricated through resin 3D printing. The entire device was made using only 39.37 milliliters of resin for a total material cost of $7.87. These droplets can be used to encapsulate medication and future guidance systems that will help direct the treatment to the correct area of the body.

During testing, we discovered a recurring defect inside the microfluidic channels that appeared as fine, hair-like resin fibers. These strands were caused by scattered light curing unintended regions of the resin during the printing process, which produced microscopic imperfections along the channel walls. These defects interfered with droplet formation and disrupted the smooth interaction between the hydrophilic and hydrophobic phases. To fix this issue, we treated the channels with tetrahydrofuran, a solvent capable of dissolving uncured or partially cured resin without damaging the printed structure.

Figure 4 – Injecting THF solvent into the microfluidic channels to dissolve resin fibers.

After flushing the device, the fibers were completely removed, resulting in clean, uniform channels and a significant improvement in liposome formation. The before-and-after microscope images included below show the effectiveness of this correction.

Figure 5 – Resin fibers clogging the microfluidic channel before THF cleaning.

Figure 6 – Resin fibers visible in the channel before THF treatment.

Figure 7 – Clean channel with no fibers after THF treatment.

Figure 8 – Clean channel with no fibers after THF treatment.

The images below show the progression of our microscope testing. The first image is a clean slide with nothing on it. The second image shows the slide with only water, which helped confirm that there were no contaminants or accidental droplets. The third image shows successful liposome production, where small circular structures begin to appear across the slide. Comparing these side by side confirmed that the device was producing real liposomes and that the structures were created by the microfluidic process, not contamination.

Figure 9 – Clean slide with no particles.

Figure 10 – Water-only sample confirming no contamination.

Figure 11 – Liposome formation visible under the microscope.

This project shows how affordable manufacturing techniques can support the development of precise, next-generation drug delivery technology.

Technologies & Tools

Project Details

Category

Research

Year

2025